First published in the NASGP Newsletter in February 2019

Recently, in Tromsø, the Arctic capital of Norway, I came across the name Carleton Gajdusek. That name took me back many years and halfway round the globe to a village in the Fore district of Papua New Guinea.

A man is standing in the doorway of his hut, clinging to the doorpost, his head nodding, before making his way unsteadily, emaciated and ataxic, to another hut. He has kuru.

Dr Gajdusek was an American virologist and he spent the last years of his life in Tromsø. He won the Nobel Prize for his work on the aetiology of kuru. Traditionally, the Fore people honoured their dead by eating their flesh, the men receiving the muscles for strength, the women being left with the brain and scrag ends. The custom of eating human flesh had already died out with the missionaries, and Gajdusek hypothesized that kuru was caused by an infective agent – he called it a ‘slow virus’– with a long incubation period. He postulated that it was concentrated in the nervous system, explaining why women were more likely to develop kuru than men. He showed that chimpanzees injected with brain tissue from dead kuru sufferers developed the disease. We now know that kuru, like vCJD and some other fatal neurodegenerative conditions, is a prion disease.

Cannibalism has a deep, transgressive and occasionally pathological fascination. Remember Hansel and Gretel? Cannibalism runs through Evelyn Waugh’s Black Mischief: Basil Seal sees a red beret in a cooking pot and realizes that he has just eaten his girlfriend. In 1991 The Silence of the Lambs attracted huge audiences and five Oscars.

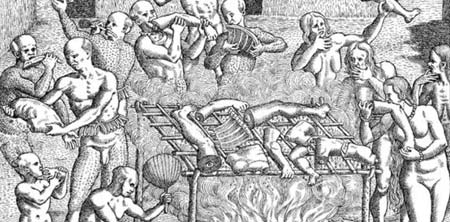

Early maps showed distant continents inhabited by monstrous beings and by cannibals. Geographical features became more accurate but the myths survived. Many of the monsters were clearly imagined. But we cannot be sure about the cannibalism. How far can early explorers’ and missionaries’ accounts be trusted? Depicting the inhabitants as savages permitted Europeans to subjugate them in the name of civilization, and to exploit their resources. Even if sometimes, as in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1609, it was the European colonists who resorted to cannibalism.

Modern techniques show that post-ice-age Britons in Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge butchered other humans.

In

the 15,000 years since then, there is uncomfortable evidence of

cannibalism almost everywhere researchers look. Though it is rarely

clear whether the victims were killed for their meat, or what the

purpose was. To honour the dead, to intimidate or punish enemies, to

celebrate victory, to stave off starvation, as a remedy or a ghoulish

gourmand treat?

I try to imagine what it might be like to butcher

another human. Of course I have cut the flesh off a human. A living

human. Making that first incision into a draped abdomen was always

breaking a taboo. Once inside I just got on with the job, perhaps the

same emotional shift happens to people desperate enough to cannibalise.

But ‘Eating people is wrong’ as Junior declares in the Flanders and

Swann song, so even those who have eaten human flesh as a last resort to

survive are reluctant to admit it.

In 1846 a wagon train set out from Missouri for California. Heavy snow trapped the pioneers in the Donner Pass for nearly four months till a relief party arrived. Some of the 48 survivors were unwilling to admit that they had survived by eating the flesh of their dead colleagues.

We don’t know what discussions went on in the Donner Pass, but when the plane carrying a Uruguayan rugby team and their supporters crashed on a remote glacier in the Andes, the survivors agreed that should they die, their bodies should be eaten to give their companions a chance of life. Two months later, 16 people were rescued. Knowledge of the survival pact mitigated the initial horror with which the events were greeted.

There is no law in England against eating human flesh, and finding a legal response reflecting the revulsion felt when psychiatrically disturbed people eat human flesh, sometimes in public, is difficult.

Still, acknowledging cannibalism would tarnish the image of true British heroes. No-one survived John Franklin’s expedition to navigate the Northwest Passage in 1845. Almost certainly the crew resorted to cannibalism, but that is something Victorian Britain didn’t want to know about. And perhaps it still makes us uneasy

Armies besiege cities to starve the population into submission. Not surprising that once the cats and the rats have been eaten, starving people consider their dead fellow-citizens as a source of food. Over half a million people in Leningrad died during the three dreadful Russian winters of the Nazi siege. Some days several thousand people succumbed to starvation and cold. Each spring the melting snow revealed cannibalized bodies.

There is no law in England against eating human flesh, and finding a legal response reflecting the revulsion felt when psychiatrically disturbed people eat human flesh, sometimes in public, is difficult.

Killing people for food is of course murder, however tragic the circumstances. In 1884 the yacht Mignonette was caught in a storm. After several days in a lifeboat two of the survivors decided to kill the cabin boy. They were convicted of murder, although, perhaps due to public sympathy, their capital sentence was commuted to a short period of imprisonment.

These days smartphones may save stranded travellers from having to take such extreme decisions to survive. But our planet is heating up and drying up. Food security is already a problem. Thousands of people from lands which can no longer support them are fleeing to more fortunate countries. In time, billions could be crowded into such space as is left, without land or resources to feed them. What might happen then?

Soylent Green, a film made in 1973, offers a scenario of a world in 2022 – only three years from now. Climate change, pollution and overpopulation have driven people into cities, and for food they rely on diminishing quantities of ‘Soylent Green’, a nutritious biscuit made, its manufacturers claim, from plankton. But demand is exhausting the supply of plankton, so where does the protein come from? Charlton Heston finds out, and as the authorities take him away to silence him he yells out “Soylent Green is people”.