First published in the NASGP Newsletter on 6th March 2023

Have you ever entered a diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy* in a patient’s notes? It’s the ICD code for broken heart syndrome. The cardiomyopathy is temporary, but the emotional effects of a break-up can last a lifetime.

When a relationship has come to an end, what do you do with the detritus? Objects which haven’t a place in the future and are too full of painful reminders to keep, yet still too emotionally significant to take to Oxfam. Stuff them in the back of a cupboard? And reawaken past pain when you find them there six months later?

Failing relationships are the staple of Agony Aunt columns, psychotherapists, lawyers and Citizens Advice. On-line services like Grief Kind, self-help groups and friends can help. But even if your negotiations on divvying up the pension and agreeing who keeps the fridge and the dog have been civil, you are left with an emotional hang-over. And the problem of what to do with the souvenirs.

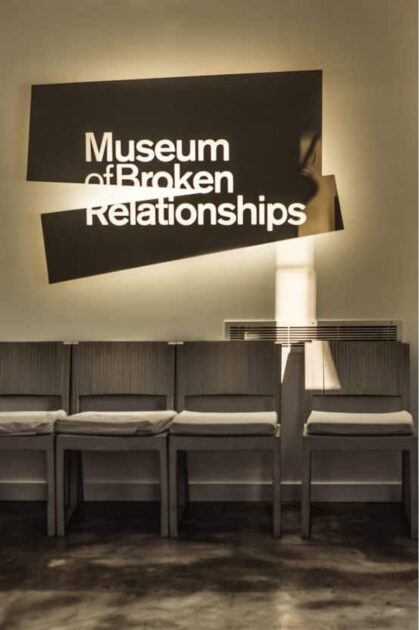

Zagreb’s Museum of Broken Relationships has an answer. They take in the emotional jetsam and display it with the story, anonymously, in the donor’s own words, in English and Croatian.

Two Zagreb-based artists had the idea after they broke up. They asked friends to

donate detritus from their own broken relationships, and the museum opened in 2006. Such is life that the collection soon amassed far more objects than the museum could accommodate, so they created a touring exhibition. It was shown in London in 2014 and its future destinations are on the museum’s website. As is the below-knee prosthesis. A nurse and the Croatian war invalid bonded emotionally as they crafted it together. He laments that the prosthesis outlasted their love.

The stories, sad, touching, and sometimes amusing, give us vivid little slices of life experience. A loving wife received the gift of an espresso machine from her loving husband. For years he loved her and the coffee she made. Then he stopped loving the coffee. Then he stopped loving her. The espresso machine is now in the museum.

A woman in Germany spent hours contemplating herself in a full-length mirror. Her husband thought it was only a mild obsession and would babysit their children when she went out with colleagues. Or, as it turned out, a ‘colleague’. When she left for good he donated the mirror to the museum. A Dutch woman had a two-month relationship with a traveller from Peru. When he moved on, he left her a plastic bottle of holy water in the shape of the Virgin Mary and a farewell note saying he had carried it on his travels to give to a new love. How bitter-sweet. But she had already looked into his backpack and found it was full of Virgin Mary bottles.

“You have to learn to live in another country in which you’re an unwilling refugee.”

It doesn’t have be a doomed relationship. As journalist Katherine Whitehorn said after her husband died, “. . . you have to learn to live in another country in which you’re an unwilling refugee.” Telling a story and donating a significant belonging can help.

Nor does it have to be lovers who part. An elderly woman, realising she was developing dementia, knew that her close relationship with her son’s wife would soon dissolve. She gave her daughter-in-law the sad news and a handkerchief to wipe away the tears. It’s now in the museum.

Some relationships end with a sigh of relief. A woman in Seoul donated a pair of rubber gloves when she no longer had to please her mother-in-law. A woman in Indiana contributed a pair of white dress shoes for the same reason.

Entropy determines that treasured household objects will come to the end of their useful lives. The sewing machine, a present when you were 16 and used to make your clothes, your children’s clothes, your grandchildren’s toys. The frilly bra you can no longer wear since your mastectomy. The toaster your parents gave you when you left home which has provided your breakfast in a lifetime of kitchens. All these are on display.

My favourite story is from a woman whose boyfriend wanted her to knit him a sweater. She bought expensive wools and started knitting, but he kept changing his mind about what style he wanted. After he dumped her, she created a

garment incorporating not only all the different necklines he had toyed with but a pattern of his tattoos. And one long dangling sleeve symbolises the unravelling relationship. Contributors can choose whether to make their stories public, and they don’t have to bestow an object. Send a thread of electronic messages recording a deteriorating relationship and the museum will put a pin in an electronic ‘map of broken hearts”. It shows that heartbreak is worldwide.

The museum offers both a witness to pain and a practical way of dealing with the leftovers, a resolution which can be difficult to find. Modern counsellors would strongly advise against the Miss Havisham option: preserving everything just as it was when your partner walked out. Equally, they would discourage the nuclear option: never again mentioning the ex or the deceased dog, the default position in buttoned-up 1950s Britain. You can let off steam by hurling an axe at a picture of your ex or venting your rage in a screamatorium – both popular in the USA. But evidence shows that the catharsis is only temporary, and the pressure soon builds up even higher.

The Museum of Broken Relationship can bring resolution for donors. For visitors it isn’t just a tourist attraction. We who visit it bear witness to pain, anger and sadness, and can take inspiration from the donors’ spirit and courage.

Thinking about social prescribing . . . what about a city break in Zagreb?

*takotsubo cardiomyopathy isn’t an eponym; it’s a Japanese word referring to the shape of an octopus trap which a ‘broken heart’ is thought to resemble.